Due to the recent situation I’ve seen some people raise concerns on property rights and threat models to ENS in general and .eth names. How can the personal beliefs of the Delegates affect ens names? Can a name be taken away from a person if they go against the values of the majority of delegates, or even a vocal minority? What if Delegates are compelled by authorities to act on a given set of names?

This is an evolving document and I welcome feedback and clarification.

1) Your registered .eth names cannot be taken from you

Per EP1 the .eth controllers and price oracles have been passed to the DAO. This grants the DAO powers like setting the price oracle or setting what the top level ETH resolves (like any subdomains have their own info attached to it, top levels domains like eth can also have. It’s not very used).

The ENS DAO does NOT control the ENS root yet. That in theory would grant it control of any top level domain, but .eth names are locked and cannot be changed.

2) The constitution is not a guarantee, but exists to give legitimacy and framework to future code changes

While article I of the ENS constitution reads: “ENS governance will not enact any change that infringes on the rights of ENS users to retain names they own, or unfairly discriminate against name owners’ ability to extend, transfer, or otherwise use their names.” it is intentionally a mutable constitution: “Article V. Amendments to this constitution by majority vote. Any change may be made to this constitution only by two-thirds majority and at least 1% of all tokens participating.”

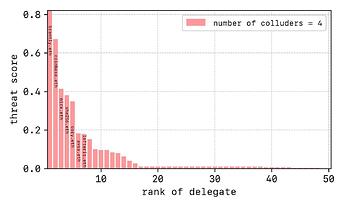

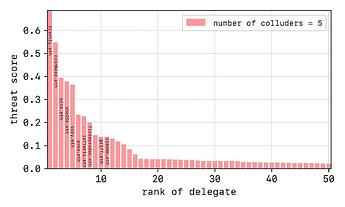

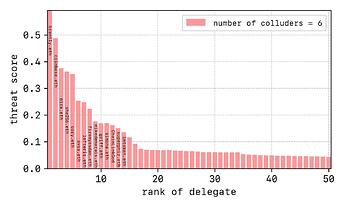

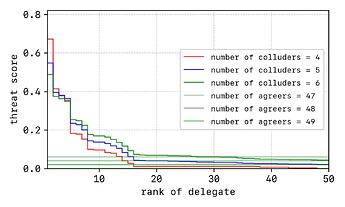

The 1% quorum on article V is intentionally low, with the idea that there would be some initial changes and then we could increase it. In Snapshot the proposal with least participation so far was voted by 1.6 million tokens, while the largest one was 4.8. The Constitution was ratified with 15M tokens. On With Tally, which is unchain, the two executed proposals got over 3M votes. The top 10 delegators have, combined 2.5 M votes delegated to them, meaning that about five people have enough votes to reach quorum for a constitutional amendment.

The constitution should always be used for legitimacy, but not as a substitute for code: if we want a hard guarantee of something we need to put it on chain, not purely as a social aspect.

In a way, the code, the tokens, the constitution represent a balance. The code has it’s own rules and the Constitution has their own edicts. If they are in sync, the community is happy and there’s a balance. If they are in sync then the community can declare one or the other illegitimate and attempt to fix or fork it. If say, the code gets broken somehow and names are locked forever, or if someone buys enough tokens to pass a particularly unpopular amendment, the community last resource is a fork–abandon the current codebase and move forward with another. This would be painful and split the community in half, but having that option is better than the project dying and it’s a good last resort of blockchain governance.

You never know when the community will split over something like what happened last week. If we want to make sure we have stronger guarantees for our core values we must:

- Protect the code by making sure that parts we do not want to change are locked

- Protect the Constitution by increasing the quorum after we are happy and decide against further amendments.

- Threat model. What is the worst that can happen?

Given the information above, here’s a scenario: if someone can buy enough tokens to pass a proposal on the DAO, they can also pass an amendment on the constitution. An attacker could do these things:

- While they can’t take names from people, they can increase rent so that names become too expensive to maintain or change the token the names are paid for to a token that is only accessible to a specific set of people (let’s say requires KYC in the US)

- An attacker could change the registration premium oracle in a way that it only accepts a specific token or NFT so as only a specific pre selected community could take them.

Now those are all hypothetical scenarios and we have to take in consideration the risk of locking up the code too soon and losing important features like L2 support or the new cheaper DNS integration. Some of that can be mitigated by having a time lock, so that if we can see the new rent is going up in 1 month, people have time to renew their names or abandon the project. What I am proposing here is simple:

We need to reevaluate possible attack vectors and mitigate them sooner than later.

Some relevant contracts:

- Base Registrar Implementation where you call to transfer a name

- ENS: ETH Registrar Controller where you register names

- DAO Access control where we vote and execute proposals on the DAO

- root.ens.eth a contract that sets access controls to ens. It’s where .eth registrar is locked permanently.

- Root multisig Address of the multisig of trusted ethereum members that is being superseded by the DAO.

Questions that I haven’t been able to answer:

Where is the “lock” in .eth happening?(edit: above)- When we change rules like the temporary premium price, in which level is it? Can it be changed arbitrarily?

- What else can it be changed? If we can change the rent to only accept ENS, how flexible is the system still?